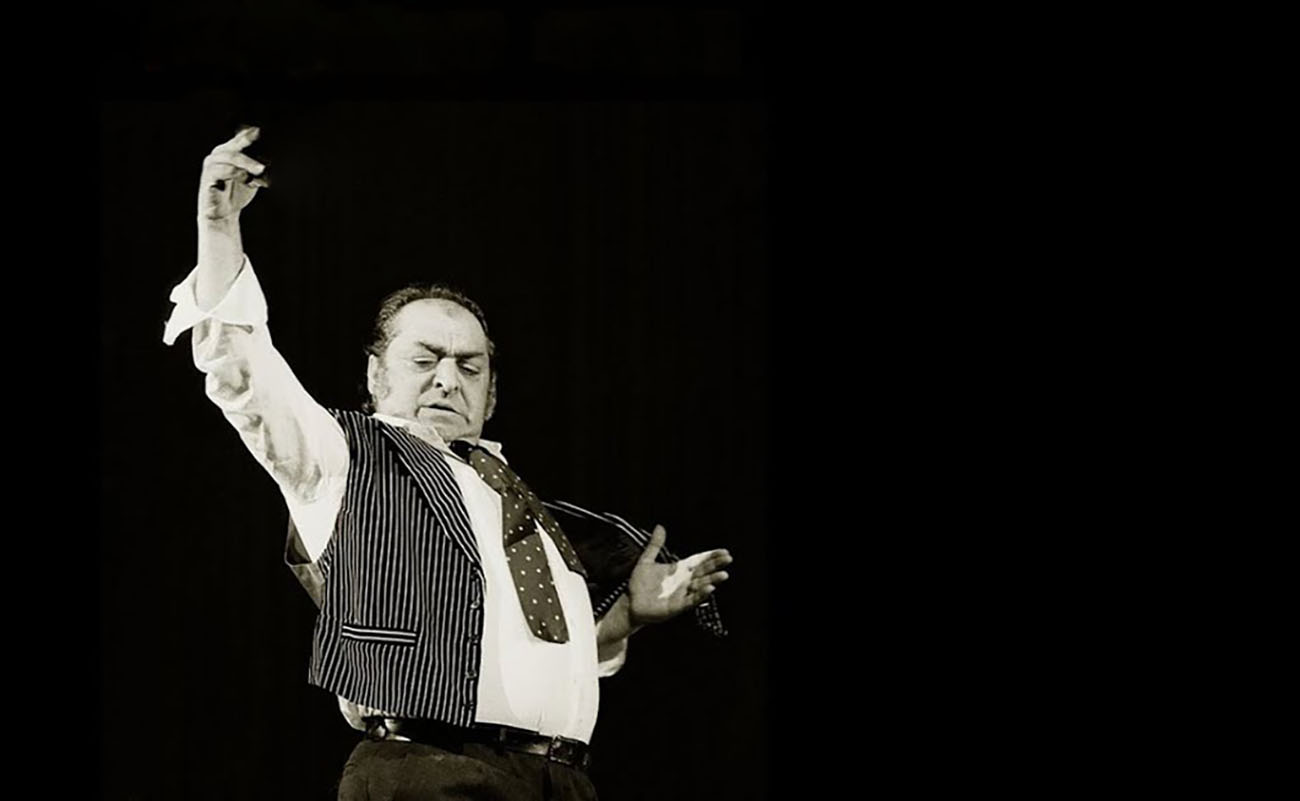

Farruco’s Dignity

The baile of Antonio Montoya Flores “El Farruco” was not cheerful, but more like a confrontation with the hardships of life. It will be a long time before a bailor with such depth and flamenco purity is born again, if ever.

I had the immense privilege of befriending the great Antonio Montoya Flores El Farruco, who in my opinion was the best flamenco bailaor of all time. And I mean bailaor. One morning at his academy in the Su Eminencia district of Seville, he told me: “I don’t sell myself for anything, or to anyone”. You may not be aware that Carlos Saura asked him to dance por sevillanas with Los Bolecos (with Matilde Coral and Rafael el Negro), in his movie Sevillanas. Saura offered him a lot of money, but despite being indebted, Farruco refused. “If you ask me to dance por soleá, I do it for free, but don’t ever ask me to dance por sevillanas”.

Farruco could have one million pesetas one day, and nothing the next, but he was always faithful to his beliefs. He died with barely any assets, having been the world’s most authentic flamenco bailaor. Without him, without his school, without his style, baile nowadays would be like almost everything else, all about money and profit. Farruco personified the essence of the old, traditional baile gitano from Seville and Triana. He was able to take his audience to another, earlier era of flamenco. Not the era of theaters, but the era of flamenco in the tenements, in the gatherings of family and friends. He was never a refined choreographer, and he was incapable of taking the easy way, something so common in our days.

«Farruco personified the essence of the old, traditional baile gitano from Seville and Triana. He was able to take his audience to another, earlier era of flamenco. Not the era of theaters, but the era of flamenco in the tenements, in the gatherings of family and friends»

He was an authentic bailaor, uncontaminated, a bit wild and with his feet firmly on the ground, pun intended. You could believe in him or not, like someone might or might not believe in God, but if you believed, he was a loyal friend. Otherwise, it was difficult to become part of his circle. He would only have drinks with people he found agreeable and who knew a thing or two about cante or baile. He had a special ability in detecting fakes who just pretended to be his fans. He could not stand fakeness or arrogance.

I can flatly deny that Farruco only liked Gypsy (gitano) bailaores. He liked good artists, those with a unique style and who were able to innovate, even if they were not gitanos from Triana or Jerez. If anyone tried to sell him a pig in a poke, he would eat the pig in a casserole. He had a hard life who made him a complicated man not easy to get along with. It was necessary to know him very well to understand his complex personality and his ways.

I closely witnessed that last years of his life, and they were hard. It could not have been any different for a man cursed with bad luck and family tragedies. Even when he smiled, his eyes had a black veil of sadness, and his smile was more like a painful grimace — like that of Tomás Pavón — than a sign of happiness. He was only happy when he danced, but not even always, because his baile was rooted in deprivations and heartbreak. Even when he danced por bulerias, a joyous palo, bitterness would not leave his face. That is why his baile was not cheerful, but more like a confrontation with the hardships of life. It will be a long time before a bailor with such depth and flamenco purity is born again, if ever.

Una estampa de gitanería,

unos pies clavados en la tierra,

un dolor que bailaba por bulerías.

Translated by P. Young