The doctor of cante jondo

Ramón Rodríguez Vargas, cantaor also known as Ramón de Trianaand Ramón el Ollero, born in Triana in 1854 and died in La Feria neighborhood of Seville in 1905, was famous not only for his wonderful singing of soleares alfareras, seguiriyas and malagueñas, but also for his extensive knowledge about cante jondo. We know that when Chacón arrived in Seville in 1885, when he was only 17 years old, he contacted Ramón to

Ramón Rodríguez Vargas, cantaor also known as Ramón de Trianaand Ramón el Ollero, born in Triana in 1854 and died in La Feria neighborhood of Seville in 1905, was famous not only for his wonderful singing of soleares alfareras, seguiriyas and malagueñas, but also for his extensive knowledge about cante jondo.

We know that when Chacón arrived in Seville in 1885, when he was only 17 years old, he contacted Ramón to learn about the old styles of Triana’s cante, which, oddly, he seldom performed later on. Ramón was an institution of Sevillan cante, a teacher, advocating for schools of cante at a time when only schools of guitar and baile existed. Although Ramón was born in Triana, he grew up outside that neighborhood and his cante was on par with other celebrated cantaores of Seville such as Antonio Silva El Portugués, Fernando el de Triana and Rafael Pareja, who also advocated the formal teaching of cante.

Young cantaores would go to Ramón’s house on Palomas street (the same street where Cuervo Sanluqueño y Frijones de Jerez lived) to learn how to sing properly. Ramón became ill with lung tuberculosis, a disease that took him to his grave, and since he was no longer able to sing at the cafés and private parties, he set up a kind of “doctor’s practice” for cantaores.

This story was told to me by the guitarist from Macarena, Antonio Peana, who assured me he heard it from the cantaor José Rodríguez El Colorao (also from Macarena), who was Ramón’s disciple. The young cantaoreswould arrive at the home of the old man from Triana, he would listen to them singing, and would write down in a notebook the defects and virtues of their performance. At the end of the session he would write down his recommended “treatment“, handing them his notes.

In those days, over a century ago, cantaores and cantaoras made an effort to learn well the cantes, and would ask the great masters to teach them. It was a different method of teaching, comparing with our days, since not even slate records existed yet. Fernando el de Triana had a tavern in Camas (a town near Seville), La Sonata, where young cantaores from Seville and other places would go and ask the old cantaor to help them with lyrics and guitar tones. That’s how he made a living, because he had a hard time after he was no longer strong enough to sing. The same happened with Ramón el Ollero, Pepe Villalba o El Portugués, among others, who never sang in theatres or companies, but only in private parties.

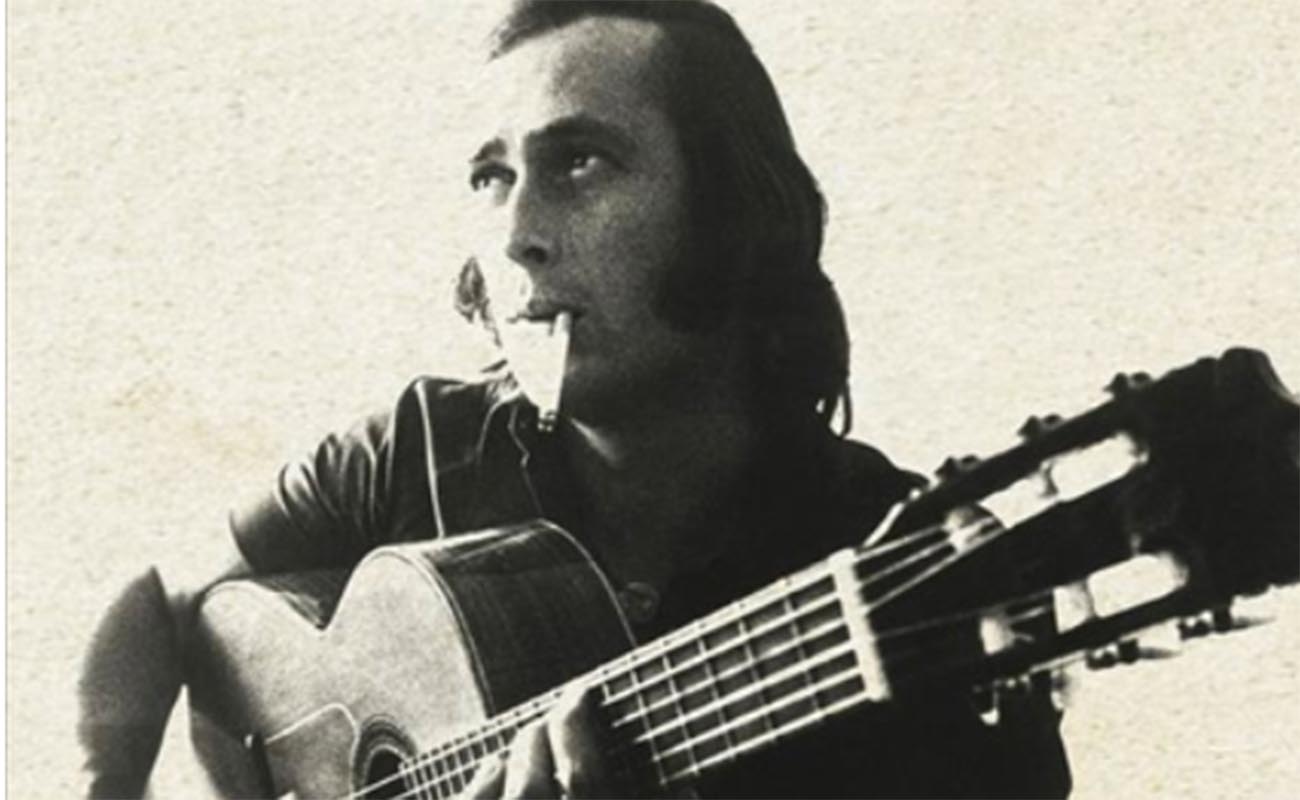

Would Fosforito, one of today’s great masters of cante, who no longer performs on stages, be successful if he set up in his house a “cante’s practice” like them? Hard to know. Antonio Mairena told me one morning at his house that he would walk from Mairena to Alcalá (about a 5-mile walk) to learn from Joaquín el de la Paula how to sing the cante de la Adonda and the cante de José El Pelao, among others. Antonio was then just 20 years old, but he was very eager to learn everything, not from records, but directly from masters who, like Joaquín, never recorded anything. Juan Valderrama also told me that when he arrived in Madrid, after Chacón had died, he would go in rooms with Manolo Pavón or José Cepero to learn how the genius from Jerez would sing the cantes de La Sarneta por soleá or how to make the seguiriya “switch” of Curro Durse.

Antonio Mairena and Valderrama were among the greatest students of cante I’ve ever known, that’s why they achieved so much success, each with their own, unique style. I won’t make the mistake of saying that today’s young performers of cante aren’t great students, because it’s not fair to generalize. Today’s methods of teaching are certainly different, just like so many other things in this art have changed. Sometimes I’m under the impression that many of today’s young performers only want to learn the bare basics to become a professional and make a living out of this art. Yet, that’s just my impression, the impression of an aficionado who, when aspiring to become a cantaor, would seek the old masters to learn the ageless trade of cante.

Translated by P. Young