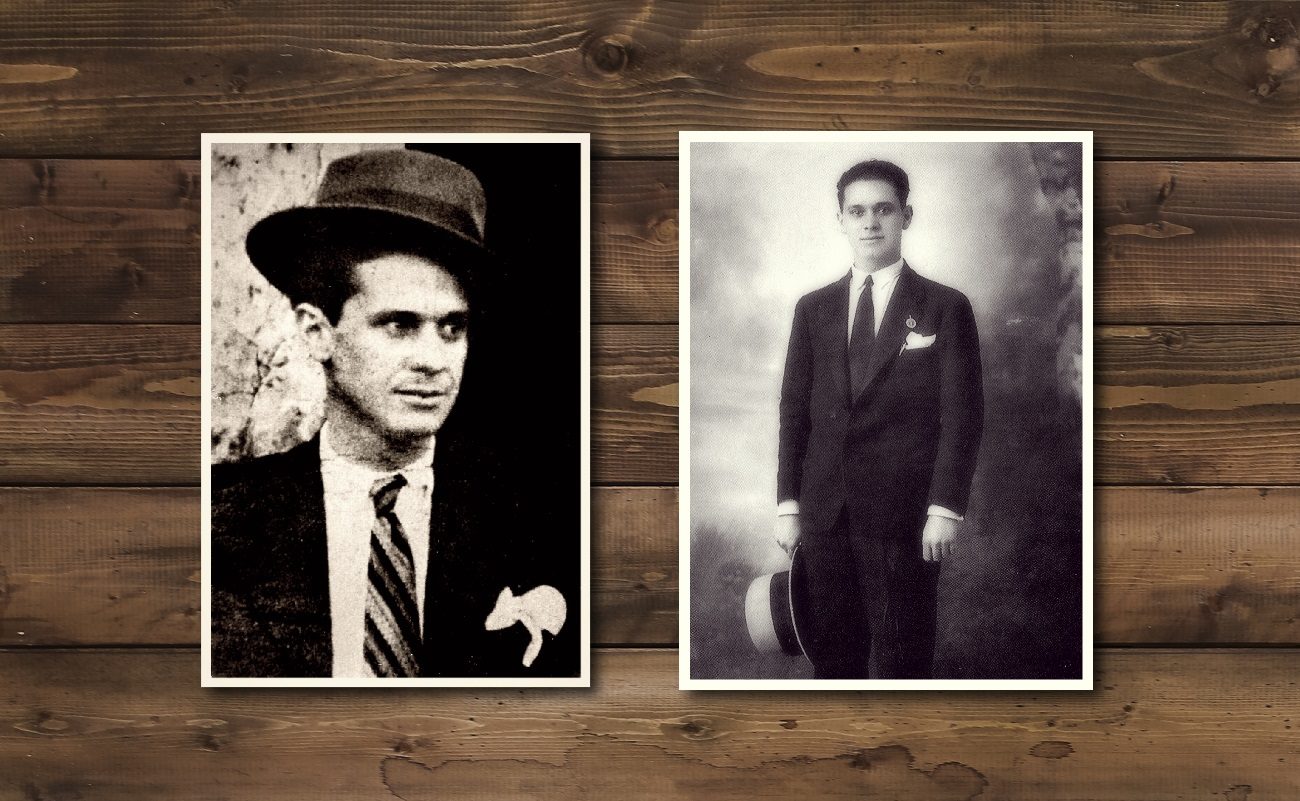

El Carbonero: a true genius

One of the geniuses of cante flamenco in Seville, Manuel Vega García, the celebrated Carbonerillo, was born on a day like today, February 8th, in 1906. He wasn’t born in the Macarena neighborhood, as it’s often claimed, but in the San Julián parish. From that same long and narrow Street that begins in San Román and ends in El Pumarejo

One of the geniuses of cante flamenco in Seville, Manuel Vega García, the celebrated Carbonerillo, was born on a day like today, February 8th, in 1906. He wasn’t born in the Macarena neighborhood, as it’s often claimed, but in the San Julián parish. From that same long and narrow Street that begins in San Román and ends in El Pumarejo were also Antonio Pozo Rodríguez El Mochuelo, the cantaora Emilia Jandra and the great bullfighter Manolo González, besides many other flamenco stars of the 19th century who worked in the cafés cantantes of Seville such as El Burrero and El Silverio.

The parents of El Carbonero were Rocío García Cuesta, who was from old-town Seville, and Manuel Vega Villar, who was originally from Benacazón (a town in Seville province), but grew up in Triana. He was a carbonero by trade, that is, he sold coal (carbon). That’s where the artist got his stage name, because as a child he would join his father in his rounds in that part of Seville, so he was called El Carbonerillo (“The Little Carbonero”). He was a cute little kid and his voice was sweet as caramel. His sisters, who worked in a textile factory on Capuchinos street, would sometimes take him to work and at lunchtime they’ll put him on a table to sing fandanguillos. Anita, one of his sisters, told me that he would make quite a stir, because he was a child prodigy of cante.

There is a long-standing controversy about the author of the fandangos sung by El Carbonero, started when an ignorant from Seville with the last name of a cantaor from Alosno started claiming they had been written by Pepe Pinto. Pepito Pinto, son of La Pinta, was a little older than El Carbonerillo, although not by much, and they grew up together in the same neighborhood of La Macarena, where El Colorao and other great cantaores were also from. They had the same influences and the same masters, and both their styles were strikingly alike, although Carbonero was always a better cantaor, with more Gypsy duende and pellizco. The way Manolo Vega sang fandangos wasn’t that of an imitator, but that of an inspired cantaor. The fact that he would be carried away by the creativity of his brother Pinto doesn’t mean at all that he was his imitator.

El Carbonero was a kid full of life, because he earned good money and had a wonderful family, but became a vulnerable and bitter man due to his heartbreaks and general problems with alcohol and drugs, which turned him into a human wretch before he was 30. The betrayal of his girlfriend took him to such a state of depression that his life ended when he was 31, wasted by TB of the lungs, an illness that took the lives of true geniuses of cante such as Manuel Torres, Paco Mazaco and Carbonerillo himself, among many others.

He died on April 6th, 1937, in the midst of the Spanish Civil War, on 51 Don Farique Street, across the old Hospital Central, which is now the headquarters of the Junta de Andalucía. Although he was just 31, he had life experiences worth a century, and not normal experiences at that, but living with vices typical of that age. Paco Lira, owner of La Carbonería, once told me that on the day of his funeral, his mother started buying all of his slate records to destroy them. Some people deny this, but I think it’s totally plausible, because the good Rocío García had suffered too much.

El Carbonero would be 113 years old today. He’s no longer with us, but his cante will remain alive for centuries, because he was a genius who made fandangos a jewel of the urban culture of Andalusia.

Translated by P. Young