Cantaor of cantaores

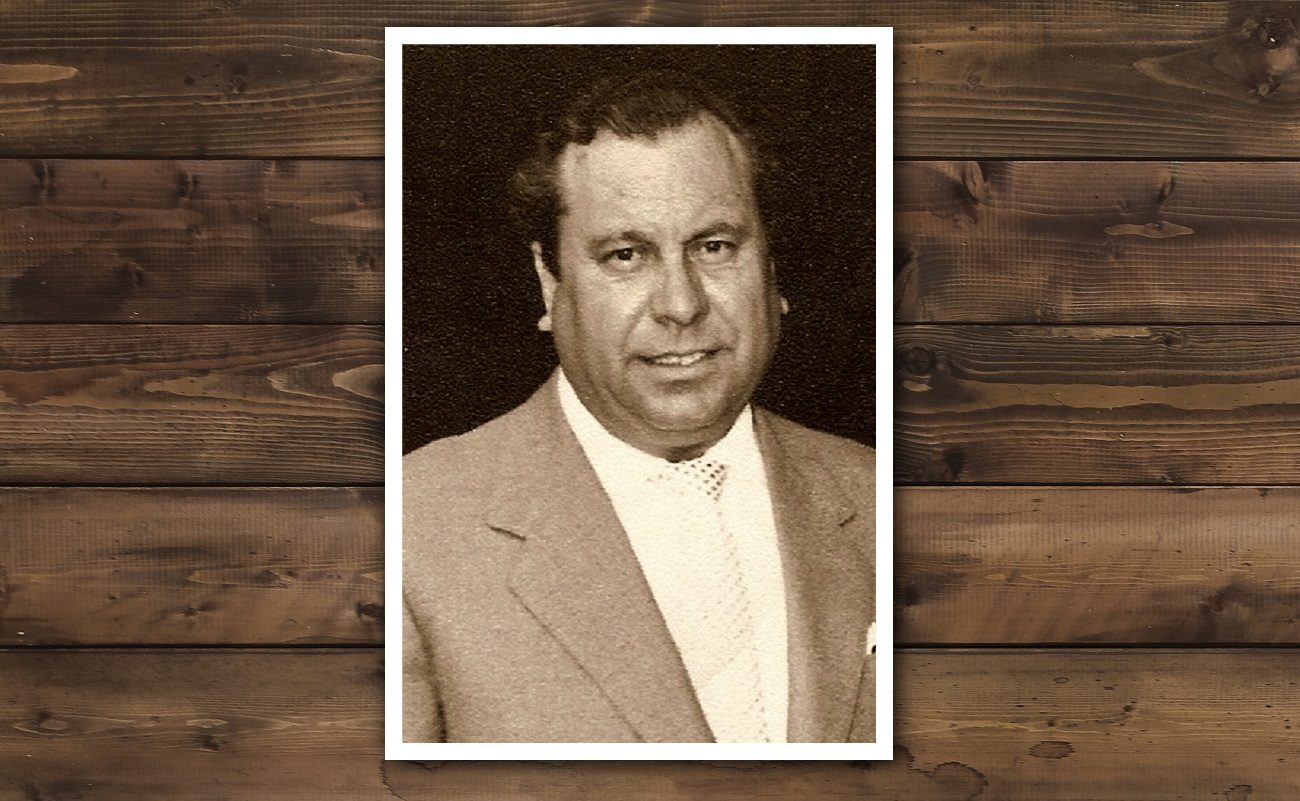

Today in our blog El Bordonazo, we bring up Antonio Tovar Ríos, known by his stage names El Niño de la Calzá or Antonio el de la Calzá. He was born in Seville, in the La Calzá neighborhood, and became a favourite of Pastora Pavón and her brother Tomás

There are cantaores and cantaoras who are admired by other artists of cante, regardless of their popularity among the general public. Tomás Pavón and Juan Mojama are two good examples of this, although there were and there are many more. Nowadays they’re called “cantaores of reference”. Today in our blog El Bordonazo, we bring up Antonio Tovar Ríos, known by his stage names El Niño de la Calzá or Antonio el de la Calzá. He was born in Seville, in the La Calzá neighborhood, and became a favourite of Pastora Pavón and her brother Tomás, among other geniuses of that time.

Born in 1913, Antonio was a child prodigy of cante, a precocious cantaor with the gifts of communication and wit. I first met him when he was 70 years old, at the now-extinct Peña Flamenca El Manantial at the Los Carteros neighborhood in Seville, where I was introduced to him by the amateur cantaor Antonio el Pichichi. I tried to shake his hand, but the master said no, not a handshake, but rather a hug. I had heard so much of him, of his greatness and also of his humbleness, that his hug was one of the greatest things I had experienced as a flamenco aficionado until then.

That same night Antonio told me about his admiration for Tomás, Pastora, El Carbonerillo and Manuel Torres, and also his admiration for living artists such as Valderrama and Camarón. The genius de la Isla was always a follower of his style and masterfully recreated his fandangos, particularly the style he created after the 1936 Spanish Civil War when, as his voice started failing, he turned the fandango around, with the invaluable help of the Sevillan guitarist Niño Ricardo, creator of some mechanisms that revolutionized guitar playing for accompaniment.

In the last tracks he recorded with Sabicas (Gramófono, 1936) and Ricardo (Columbia, 1943) we can see that spectacular change which set the foundation for a new way to perform the fandangos naturales, lacking the characteristic pre-war gloss, but having a greater depth and feel, more “jondura y pellizco”. I talked with Antonio that night about this change and he told me “sometimes, loosing our abilities forces us to reinvent ourselves”. Antonio influenced not only Camarón, but also Pansequito, Rancapino and Chiquitete, among others. In his old age, Antonio was very proud that young singers would follow his very personal style of cante.

Yet, el de la Calzá wasn’t just a fandanguero, but he was also able to sing malagueñas, tarantas and buleríaswith great skill. When the Spanish Civil War started he was already a big star, having had great success at the time of the Ópera Flamenca with Marchena, Cepero, Vallejo, Canalejas, Pepe Pinto and Pastora. At the time of the military coup that started the Spanish Civil War, he was in Jaén with the company of Pepe Pinto and Niña de los Peines, but instead of moving to Madrid like Pastora and Pepe did, he stayed put in Jaén, because he knew right there that Seville was one of the cities most severely punished by the fascist coup, where blood flowed on the streets like rivers.

Certainly, all the distress he endured in Jaén, unable to return to Seville, affected his singing style, changing it, and he continued to have great success in the company of Manuel Vallejo and also in the company of Pepe Pinto. However, he almost lost his voice, which no longer had commercial appeal, forcing him to leave the stages, unable to compete with other artists, and he spent his last days running a concession stand and singing in the odd party. Such was the end of one of the best cantaores of Seville, creator of a unique, personal style that today is followed by young artists such as Rancapino hijo, to name just one example. Antonio Tovar Ríos, the great Niño de la Calzá, passed away in 1981.

Translated by P. Young