Back in the city of Málaga

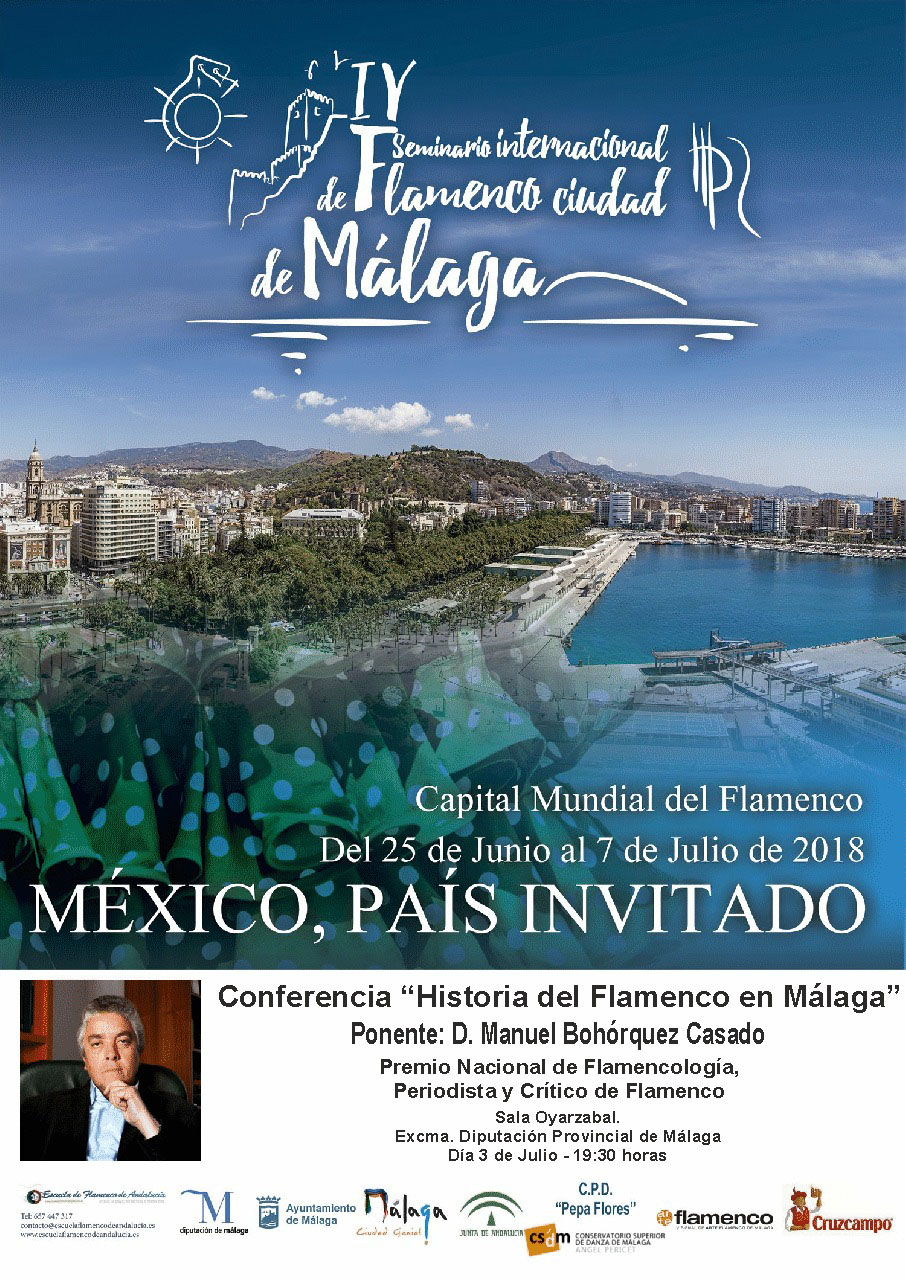

Tomorrow, Tuesday July 3, I’ll be giving a lecture at the Oyarzábal hall in Málaga’s provincial council, located at Plaza de la Marina. I’ll be doing this within the scope of the International Flamenco Seminar organized by the Escuela de Flamenco de Andalucía, a project that already is more than a project. I’m excited to show a good amount of documents

Tomorrow, Tuesday July 3, I’ll be giving a lecture at the Oyarzábal hall in Málaga’s provincial council, located at Plaza de la Marina. I’ll be doing this within the scope of the International Flamenco Seminar organized by the Escuela de Flamenco de Andalucía, a project that already is more than a project. I’m excited to show a good amount of documents about 19th-century flamenco in general, but particularly about artists from Málaga, or who were related to this city, such as El Planeta, his nephew Lázaro Quintana, Silverio Franconetti, Fillo Jr. and La Andonda, Paco El Gandul and Tomás El Nitri, among others. This lecture is the result of years of research and I celebrate the fact that I’ve been asked to do it in Málaga, for all I’ve researched in this city which is so beautiful and so flamenca, even as all the glory is often taken by Seville and Cádiz, or vice-versa.

It’s not that I want to downplay the impact of the so-called Lower Andalusia, but Málaga had a huge importance in the birth of flamenco, due to its rich folklore and specific artists of the 19th century who ended up there following the money of Heredia and its many cafés cantantes. In the 1800s, Málaga became the financial capital of Spain, and this contributed to a lively flamenco scene in the theaters and cafés cantantes. Besides El Planeta, the cantaor from Cádiz who settled in Málaga in the 1830s and who died of old age in 1856 on San Juan street in downtown Málaga, it’s very important continuing to highlight the great star of that province of Andalusia, Juan Breva, whose 100th anniversary of his death is celebrated this year.

Besides Breva, another important cantaor of Málaga was Canario de Álora, who revolutionized cante por malagueñas and who was killed in 1885 by the father of Rubia Colomer. Another great artist from Álroa who came to Seville with Canario in 1884 was El Perote, who married Lola Pérez (a bailaora who was daughter of Maestro Pérez) and who also died young, without a doubt as a consequence of the harsh life artists led in those days. We can’t forget mentioning the greatest malagañera of that province, La Trini, whose life story still needs to be told, particularly where, when and how this great maestra del cante ended her days.

I’m happy to go to Málaga, because even if I’m from Seville, I acknowledge the importance of this city in flamenco. It’s been years since I last gave a lecture in Seville, where, sadly, less and less people has any interest in the history of our art. Many of Seville’s flamenco stars have been forgotten, such as Frasco el Colorao, Lorente and, above all, Silverio Franconetti. My fellow Sevillians don’t really care to know anything about them.

Yet, the people of Málaga has shown an increased interest about the pioneers of this art. Months ago I was at the Peña Juan Breva and now I’m back to talk about the same topic: flamenco pioneers not just from Málaga but also from other provinces in Andalusia. In fact, the Peña Juan Breva commissioned me to write the biography of El Planeta, and I’m working on it, although I haven’t had much time to finish this book.

It will be a great pleasure to share all these documents with the people of Málaga tomorrow at 7:30 PM and have a good chat about this art we’re so passionate about.

Translated by P. Young