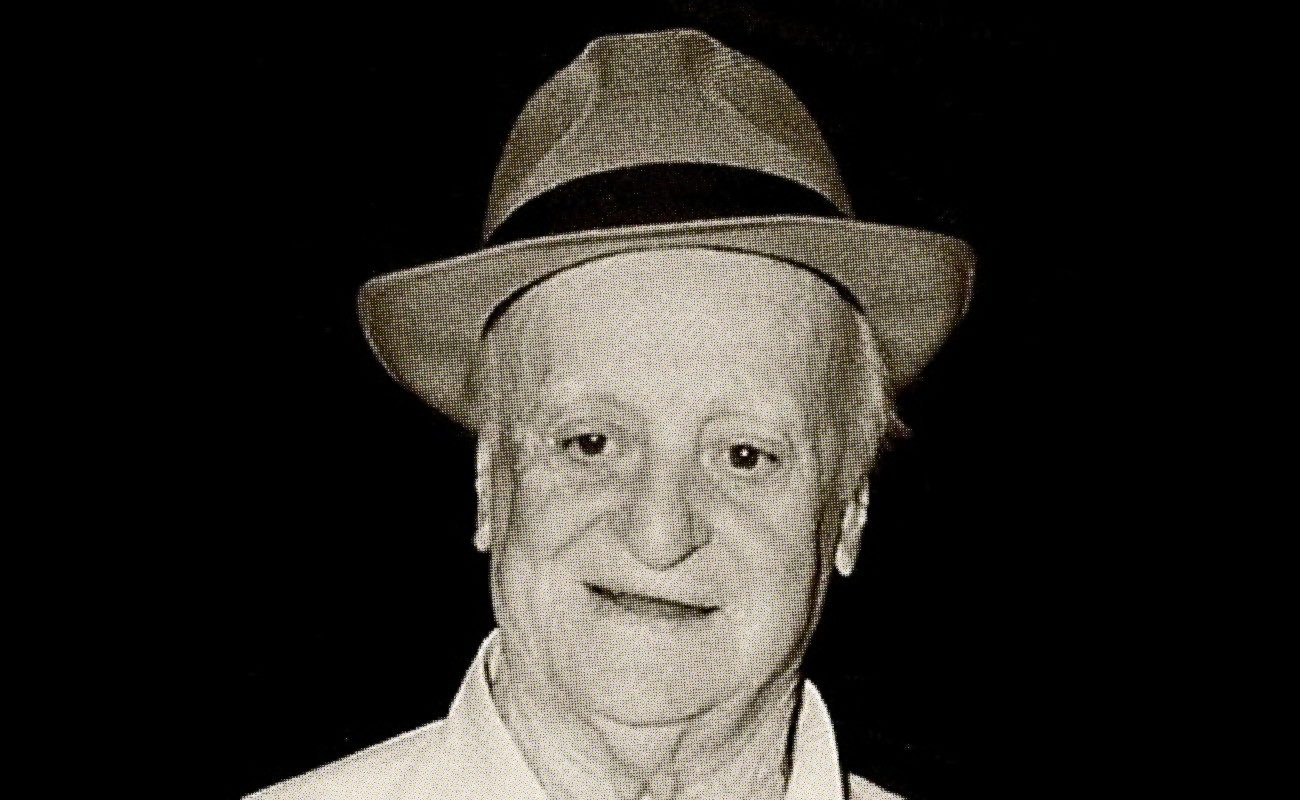

Antonio El Arenero: the potter’s eco

I’ve been researching the cante and performers of Triana for half my life and I’ve been very lucky to have met many of the good artists of that renowned district of Seville

I’ve been researching the cante and performers of Triana for half my life and I’ve been very lucky to have met many of the good artists of that renowned district of Seville, where I lived for almost eight years, in the Voluntad neighborhood to be specific. Yet, before living there, I used to work there too, since I was 13 years old, first at Antonio Tocino’s painting workshop on Constancia street, and sometime later at Ángel Sierra’s tailor shop, on Trabajo street. I even married a woman from Triana, in 1986, at the Marineros Chapel, no less.

One the cantaores I was best acquainted with was Antonio González Garzón, El Arenero, whom I consider to be one of the best performers of the cante de El Zurraque, that is, the soleares alfareras (potter’s soleares). I won’t say he was the most versatile in that style, but he had a very peculiar voice and unique fortitude. Those soleares are meant to be sang rather slowly, and performing them doesn’t require an outstanding skill. Indeed, many cantaores tried to include them in their repertoires and record them for their albums, failing miserably (no need to say names).

Apparently, it was the mythical Ramón El Ollero, born on Procurador street in Triana, the first one to excel in these soleares. Ramón had an encyclopedic knowledge about all sorts of cantes of his time (the late 1800s), but his main imprint was left of the soleares alfareras. El Arenero was born twenty years after El Ollero’s death in Seville, in 1905, so he never had the opportunity to listen to him. He would learn about this cantefrom the oldest cantaores in the district, instead. Antonio himself told me one afternoon in a bar of Triana that there were “many made-up stories about Ramón”, because many people who had never heard him sing would talk about him.

Besides, Antonio was a late professional, his true occupation being arenero (sand dredger), the origin of his stage name. Antonio would tell me that when he was a kid, back then in the 1930s, cante was something learned in taverns and in gatherings of aficionados, and that he always heard good things about El Ollero, particularly from the cantaor Emilio Abadía (also from Triana), who could have never heard Rodríguez Vargas (El Ollero) either. Emilio was born in 1903, so he learned about Ramón’s cante from other cantaores of his time and from old aficionados, such as Garfias, for example, the cantaor and watchman of Castilla street.

What is certain is that El Arenero would have been able to listen to good performers of that cante, such as the above-mentioned Abadía, Manolo Oliver, El Sordillo and Domingo el Alfarero, who although not as outstanding as Ramón, were his disciples. I heard Antonio El Arenero perform in gatherings of aficionados (such as those held in the house of Triana’s dentist Paco Parejo, on Alfarería street), and also on stages too, although at the time he was elderly and his voice was worn-out, because he was an inveterate smoker. This dwindling of skills forced him to sing in a quiet voice, with some incredible low notes and a bullfighter’s measured focus. He had a wonderful vocalization and the tune of his soleá was perfect, even as his compáswasn’t the best.

He performed until 2004, the year when he died, after he became one of the main references for Triana’s cante, a role model for other cantaores such as Chiquetete, Paco Taranto and Márquez el Zapatero, among others. Few cantaores who became professional at such an old age achieved such fame, particularly in Triana. El Arenero is today renowned for his cante por soleá, although he also sang por seguiriyas, managing to master A un toro de plaza, the cante of La Josefa. Yet, we aficionados will always remember him for his sweet, sober and deep soleares alfareras, and for these lyrics that he sang often:

Sordo como una tapia

y ciego de nacimiento.

Más valía que mi mare

me hubiera parío muerto.

Deaf like a stone

And blind from birth

I’d rather my mother

Have me born dead

Don Antonio was quite a cantaor, and quite a character. A first-class entertainer and, above all, a loyal friend.

Translated by P. Young