Among experts

There are so many things we can learn from artists and great aficionados that we cannot learn anywhere else. What I wonder is who, among today’s artists, is able to talk about cante just like Mairena, Valderrama or Naranjito could.

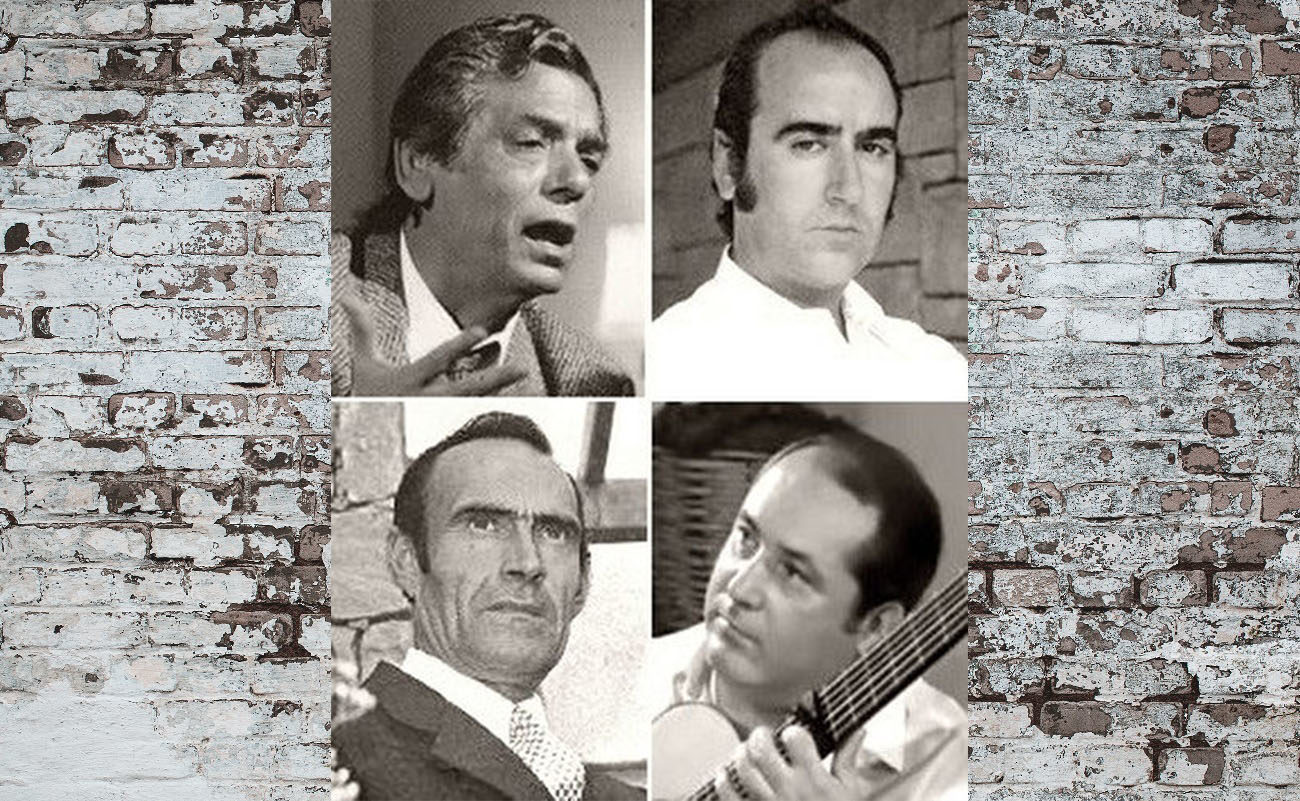

I’ve always been interested in cantaores and cantaoras who know a lot about cante, something which I consider to be essential in order to be a good performer. One thing is to have a good, beautiful voice, with duende, and another is to be a good singer. One evening I had the great privilege of socializing with Antonio el Chocolate, Naranjito de Triana, Eduardo el de la Malena and Pies de Plomo (the father of José el de la Tomasa) and this topic came up. Checking some notes I took that day, I discovered many interesting details about how the artists talk about things we critics are unaware of, particularly those of us who aren’t musicians.

We were in the house of a good friend in Coria del Río, overlooking the Guadalquivir river, and El Chocolate got started talking about all what his good friend Pepe Marchena knew about cante, although at one point he mentioned that the master “knew cante in his own way”. Naranjito asked Chocolate what he meant by “in his own way”, and Antonio, always lively, explained: “Look, Naranjo, Pepe was unique, but sometimes he didn’t know how to explain things and he would make stuff up on the fly. For example, he would be talking about the cante of Ramón de Triana, El Ollero, and since he had never listened to him, and Ramón had never made any recording, he would say things like Pareja or Chacón had told him that Ramón’s cante was this or that way. You know what? Pepe could sing soleares with fifteen or twenty different lyrics, because he had a prodigious memory. Yet, he made stuff up, he was very given to it”.

Naranjito de Triana knew more about cante than all that has ever been written about it, and, unlike Marchena or Chocolate, he knew how to explain things, sometimes with a guitar in his hands, because he was a very good tocaor, besides being a luthier. He asked to borrow Eduardo el de la Malena’s guitar and explained, in minute detail, how were Ramón’s cantes, from a musical’s perspective. “Emilio Abadía told me that El Ollero would setup cantes for Chacón, telling him stuff like ‘La Gómez would start in the second compás, when singing por soleá’. In those years there were cantaores who, before they started singing, would take the guitar and tell the guitarist how they should play, in which fret they should put the bridge and even how they should start and end the compás”.

Pies de Plomo wasn’t very talkative and, since the conversation had become quite technical, he didn’t say anything. Until Antonio el Chocolate started talking about Manuel Torres and his brother Pepe, about Mojama and Tomás, then Manuel Giorgio (Pies de Plomo’s actual name) finally joined the conversation. “My father-in-law, Pepe Torres, told me that Frijones also played the guitar and sometimes he would explain things to the professional guitarists. He said that Frijones once told Antonio Pérez, the eldest son of Maestro Pérez: ‘Those tunes are for Gayarre, give me just what I need”. Interesting expressions, some technical and others not so much, that should be analyzed.

It was in that evening when I first heard about El Planeta’s seguiriya, which, according to Pies de Plomo, became known thanks to Pepe Torres, who recorded it. Pies de Plomo explained: “That cante was rescued from oblivion by the father of Manuel and Pepe Torres, Juan Soto Montero, from Algeciras, a butcher by trade. He was also a great cantaor, but not professional. One evening, Pepe Torres, who was living at La Alameda, sang it for Antonio Mairena, who encouraged him to record it”.

A while ago, a great aficionado from Alcalá de Guadaíra sent me a recording where Antonio Mairena explained how he discovered that cante, El Planeta’s A la luna le pío, which matched Pies de Plomo’s version. Yet, just three days ago, an aficionado in his 90s, Rufino Pérez, who grew up in La Alameda, told me that this cante was performed by Caracol’s maternal grandfather, Gregorio Juárez Monge, from Málaga, who was a grandson of El Planeta who, indeed, lived many years at La Alameda and whom I located in Seville’s census records from the early 20thcentury. Rufino also confirmed something I published many years ago: A la luna le pío was in fact an old funeral toná (Toná del Entierro) from Málaga, sung among the mourners during a burial.

A la luna le pío,

La del alto cielo,

que me saque a mi pare

de donde está metío,

que verlo camelo.

(To the Moon

In the high heaven I ask

To take my father out

From where he’s in

‘Cause I want to see him)

Take him out, not from prison, but from the coffin. There are so many things we can learn from artists and great aficionados that we cannot learn anywhere else. What I wonder is who, among today’s artists, is able to talk about cante just like Mairena, Valderrama or Naranjito could.