A dangerous occupation?

Once I talked with Camarón, on the occasion of the release of his album Soy Gitano (1989), in Cádiz, and he told me. “You really love Enrique, don’t you?”. We all know which Enrique he meant.

A good title for a book would be How to be a Flamenco Critic and Not Die Trying (here’s my suggestion for a daring publisher). It’s one of the hardest professions out there, and one of the worst paid, specially for someone independent and honest (otherwise it’s a matter of just going along with whatever people want to hear, then there isn’t any problem). When I decided to become a flamenco critic, I took many things into consideration, because I knew what I was getting into. I always found peculiar the relationship between the flamenco critics and the artists in the 1970s, and I have to say I didn’t like it at all. So, from the start I tried to avoid behaving like certain people, at least when it came to behaviors that I really objected to. I don’t know if I’ve succeeded in that or not, but I’ve tried.

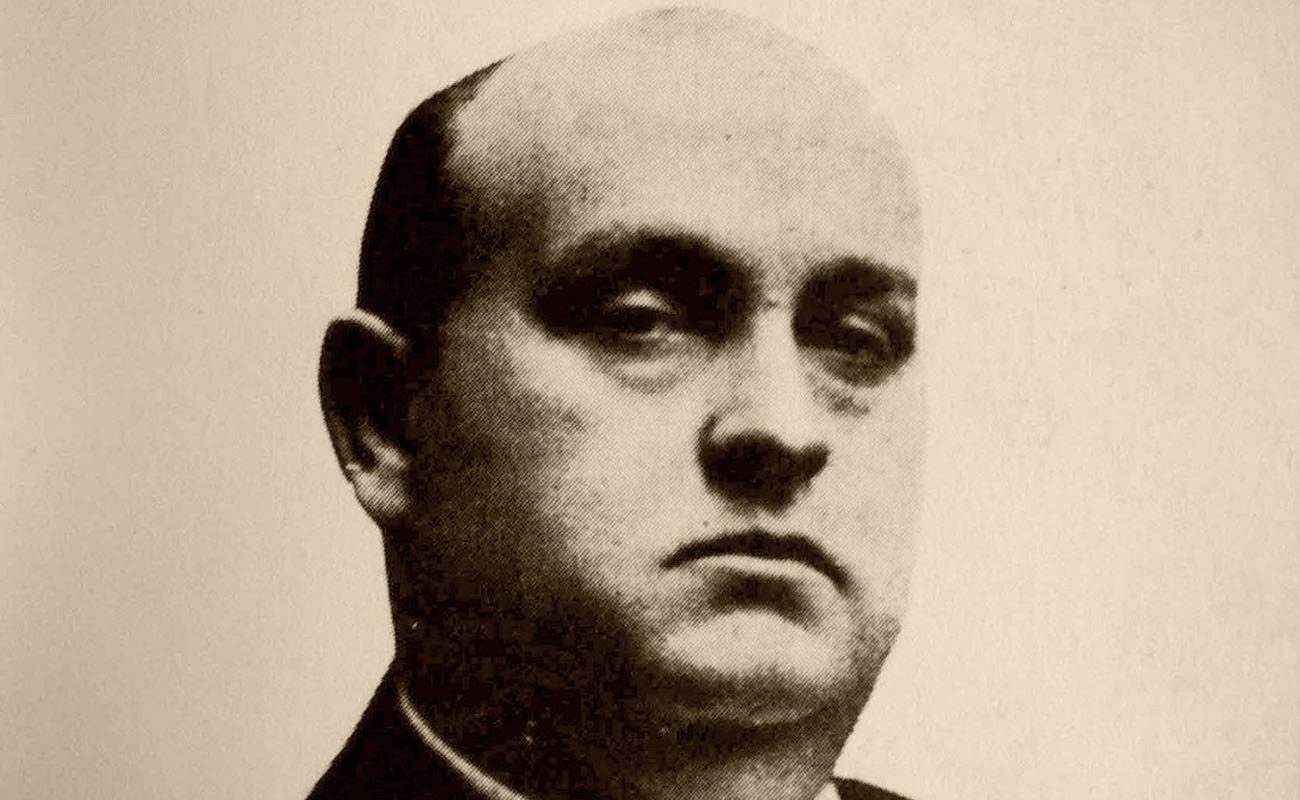

It’s not easy avoiding being trapped by the charm and charisma of flamenco artists, particularly when one is also a flamenco aficionado, and not just a critic. Any true aficionado would have their personal preferences, and it’s hard to hide them. That’s why there have been critics biased towards Caracol, Mairena or Marchena, as well as towards Camarón, Morente or Menese. It’s something very human and natural. Sometimes I’ve wondered how the relationship between artists and critics in the 19th century would have been, as it was a time when cantaores would carry knives and even guns. Just seeing the photographs of some those artists of those days gives me the chills.

The writer Demófilo had a few problems in Triana when he published his celebrated book Cantes flamencos (1881), where he mentioned many artists, but omitted others. The same happened to another writer, Fernando el de Triana, when he published his book Arte y artistas flamencos (1935), as he left out or didn’t pay much attention to certain important artists. Fernando was broke at that time and, as Juan Valderrama once told me, he would ask some artists for money in order to feature them in his book (although probably he didn’t demand money from them all). Valderrama reportedly was himself asked for money, even as he was rather well-known at the time. The cantaor and writer Rafael Pareja, from Triana, didn’t have these problems because his memories were published after he died, otherwise he would have had issues, too.

Flamencos love to be featured in newspapers and be praised by the critics, yet they don’t like when we point out their faults because, as they say, we take the joy away from their children. I remember once when I wrote an article about a very bad guitarist, although in a very respectful way. One day he saw me in a peña in Seville and asked me to go outside to settle the score. He took the newspaper clip from his wallet and asked me if I had written that about him. I said yes, of course, and he said that because of that article he had lost forty gigs in the festivals that summer. Forty gigs! Not even Juan Habichuela, the great master of the guitar, would have had that many bookings. In the end, we sorted out the matter over a few beers, with me apologizing, but it was a tense night. That’s just one story out of thousands I could tell.

As far as I know, no flamenco critic has ever been killed by an artist, although some have been slapped, no need to say names. In general, the relationship between critics and artists is good and proper, at least in our days, perhaps because now being a critic is a more professional undertaking, comparing with the old days, and there is always respect among professionals.

Is it a dangerous occupation to be a flamenco critic? Not at all, at least that’s what I think, and I have almost four decades of experience doing this. Flamenco artists are generally good-hearted and they usually respect our work, and I’m not saying this to sugar-coat anyone’s bitter pill. However, artists are more annoyed by good critics about other performers, than by bad critics about themselves. They’re very jealous. Once I talked with Camarón, on the occasion of the release of his album Soy Gitano (1989), in Cádiz, and he told me. “You really love Enrique, don’t you?”. We all know which Enrique he meant. One Enrique who, by the way, Camarón truly admired.

Translated by P. Young