The settlement and the “cortijos”

Hay días que es mejor no salir de casa porque las noticias te acosan y revuelven tu alma ya afligida por el inexorable paso del tiempo.

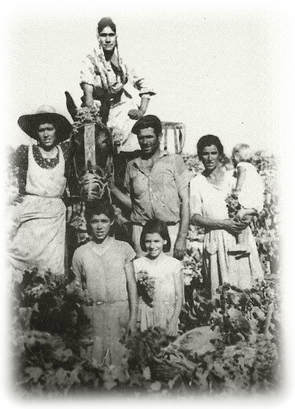

Gypsies abandoned their nomadic lifestyle in the Lower Andalusia earlier than in the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, in great measure due to the vineyards and the cortijos (farm estates). Demand for cheap labor gave the Gypsies access to work in the fields, and that in turn allowed them to earn a small salary, giving them reliable access to food and the opportunity to interact with non-Gypsy families. At the cortijo, they had at their disposal products that they could hardly get before, such as bread which, according to my paternal grandfather, was always hard, and was used as the main ingredient in many of the dishes.

Food, considered as part of the salary, included vegetable stews with a little oil and other ingredients such as bacon, which provided a considerable amount of energy. The seasons at the cortijos used to be long, sometimes lasting several months, thus someone had to be sent away to buy supplies with whatever little money they had. It was often necessary to buy on credit and pay the storekeeper at the end of the season.

The cortijos provided a roof or a place to sleep, a shelter for the cold winters and hot summers, and also a place to relax in the little spare time they had. This place was called the gañanía (labourer’s farmhouse), and, accordingly, the farm labourers who stayed at the gañanías were referred to as gañanes.

May parents and my grandparents worked in the fields since they were children. They used to tell me countless stories about their lives. Their parents and grandparents also worked in the fields. My paternal grandfather was a manigero (the foreman responsible for the gang of gañanes) and kept, in a large chest of drawers, bacon (salt-cured to preserve it) and, if they were lucky, some meat.

The lunch or midday meal was taken to the tajo (the place in the cortijo where labor was taking place at the moment), if it was far from the gañanía. The person in charge of bringing food was called the gazpachero, who also brought water. Both the food and water were transported by donkey or mule in clay jugs. Water and gazpacho were kept fresh. The mouth of the jugs were rather small and food was kept quite hot.

At the gañanías there was one or two cooks, according to how many people were working at the time. The kitchen would have one cooking fire pit, two at most. Dinner took place at the gañanía, prepared by the women and, sometimes, in the meantime, the heart of a lettuce would be eaten whole, seasoned with a little salt and vinegar and, if the budget allowed, wine, from Jerez of course.

Work was hard, and fatigue was apparent. Yet, my mother would say that not a lot was needed to feel somehow happy and, almost always, people were in the mood for laughing, singing and dancing.

Knowledge about the products of the countryside, which the Gypsy people had acquired while they were nomads, and then interacting with the people in the area of the gañanías, allowed the fusion of both styles of cooking, making those stews popular until our days.

From “La Cocina Gitana de Jerez”, por Manuel Valencia (EH Editores, 2006)

Translated by P. Young