Flamenco artists and their fear of flying

Generally speaking, flamenco artists are terrified of flying, even as they have travelled in airplanes endlessly. Hundreds of lost contracts and careers down the drain due to aerophobia

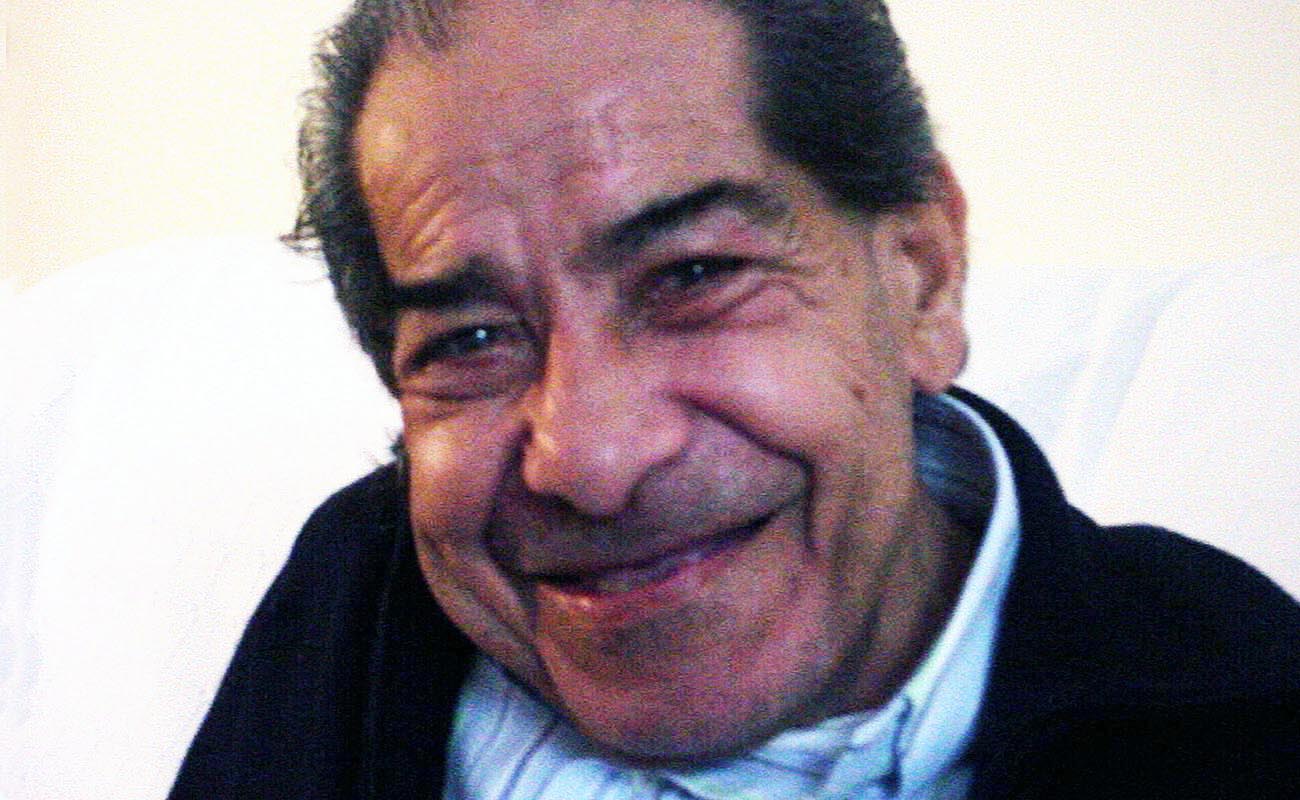

It’s not something I’ve heard, it’s something I’ve lived. Generally speaking, flamenco artists are terrified of flying, even as they have traveled in airplanes since air travel has existed. In the old days, ships were the most common means of transportation for flamenco artists. Antonio Gades once told me that, when he was with Pilar López, he got a contract to perform in Japan, and they went by ship. The trip to get there took three months, they worked for fifteen days in Japan and then back to Spain after another three-month trip. Quite something. In the five years I toured with Antonio we travelled continuously by plane, at the time when smoking was still allowed in airplanes, except on Japan Airlines, although we smoked in their airplanes anyways. Fifteen-hour long trips to Hong Kong, Jakarta, Santiago de Chile or São Paulo. Five years travelling in airplanes. I was never afraid of flying, but there were flamenco artists in our Company who had flown around the world dozens of times, for over thirty years, and yet were absolutely terrified the moment they boarded an airplane. I remember one time when our plane was shaking up and down as we climbed to go over the Andes, having taken off from Chile. The plane had to first gain altitude overflying the Pacific Ocean to be able to cross that mighty mountain range. As we crossed the snow-capped mountains, someone thought it was funny to remark “Here was the air crash described in that book ‘Alive’!”. The pale faces of the flamenco artist were something to behold.

I have known artists — although I’m not giving names out of respect, even as I’m sure most readers will know a few — who had hindered their careers because of their adversity of flying. If a contract to perform in (say) Berlin came up, they would go by car or train, but if the trip required air travel, no way, they better hire someone else. Hundreds of lost contracts and careers down the drain due to aerophobia. I admit that I love seeing the earth from the air. I always pick the window seat and identifying landscapes and cities from the sky is a hobby I’ve enjoyed since my childhood. My love for maps runs in the family, and from an airplane we can enjoy seeing the map coming alive. There is also something to be said about easing the fear of flying by being able to see outside, as I feel anxious when there is turbulence and I cannot see outside. I remember a trip I made to Indonesia in a 747 Jumbo Jet, bursting at the seams with people, creaking as it crossed the imposing Himalayas. It felt like it was going to break apart. I was not afraid, I was in absolute panic.

For many, whisky was the best way to alleviate the fear of flying. Getting on a plane after downing gallons of scotch used to be foolproof, with the resulting snoring heard all the way to Pamplona. Cards were also great travel partners, allowing us to forget that we were flying at thirty thousand feet and five hundred miles an hour, with an outside temperature of minus fifty degrees. Yet, singing was the ultimate remedy. At the beginning, the other passengers would feel fortunate to be able to enjoy live Spanish singing, but by the fourth song they were just tired of it. It didn’t matter, what was important was to keep the fear away and escape the panic that flying creates in some heads and hearts. I get that it must be unbearable. The superstitious beliefs characteristic of flamenco artists conspired against us in such moments. And don’t even think of mentioning the petenera, that beautiful flamenco palo — recorded by flamenco icons such as Manuel Torres, Pastora la Niña de los Peines, Camarón and Morente — which has an unfair and misguided reputation for bad luck, even as it has never harmed anyone. Be prepared for nasty stares if you ever utter that name inside an airplane.

«Flamenco artists had a really hard time, some more than others. Any unexpected movement was feared, and I would come up with aeronautic theories about how airplanes were built to withstand the most extreme weather, to no avail. They would try to smile, hiding the cruelest panic, grabbing my arm and painfully squeezing it at any sudden movement»

I remember a tour in Brazil that took us to a dozen cities, and since that marvelous country is a continent in itself, air travel is necessary to move from one city to another. From Rio de Janeiro to Manaus, in the middle of the Amazon, it’s three hours of nothing but rainforest, with bare logging spots every ten minutes followed by a thick jungle that swallows roads soon after they’re cleared. I really don’t know why, but in that country pilots seldom descend gradually as they approach their destination, which seems to be the norm elsewhere, but rather, three minutes before touch down they dive in, leveling off a hundred feet above ground just before touch down. It’s a terrifying technique, and I don’t need to describe the look in the faces of my dressing room companions in those moments. It was quite something.

When we went to Cuba (Gades was a friend of the Castro brothers and his ashes are interred in the Panteón de los Héroes de la Revolución Cubana) we travelled from one city to another in the so called “patitos”, little windowless airplanes that creak frightfully when taking off. From Havana to Guantanamo it’s five hundred miles of hair-rising turbulence. That tour, documented in two programs that can be watched here and here, was wonderful, but the fear we experienced flying over the Pearl of the Caribbean was unforgettable. Generally speaking, the boys and girls in the dance troupe didn’t show any fear, as their generation is from a time when flying was part of any artistic career, but the older flamenco artists had a really hard time, some more than others. Any unexpected movement was feared, and I would come up with aeronautic theories about how airplanes were built to withstand the most extreme weather, to no avail. They would try to smile, hiding the cruelest panic, grabbing my arm and painfully squeezing it at any sudden movement

I don’t want to even think about how it was in the 1950s and 1960s crossing the Pond, enduring the fear for endless hours over the ocean until the destination was reached. Yet, after landing safely the worst was not over yet. The return trip still awaited. Such is life.

Translated by P. Young

→ Read here previous articles by Faustino Núñez in Expoflamenco