Farewell to Manolo Sanlúcar, our greatest flamenco artist

The master Manolo Sanlúcar, 78, passed away this Saturday, August 27th, at the Jerez Hospital. Manuel Muñoz Alcón, from Sanlúcar de Barrameda: the child who made real his dream of turning our Andalusian flamenco music into a universal art genre.

To be Andalusian is more than having been born in the south of Spain. A lot of people have been born here, but there aren’t as many Andalusians as the census figures would make us believe. To be truly Andalusian is to feel proud of it and to stand up for this land against those who think it is just Spain’s backyard of music and fun. To be truly Andalusian is knowing its history and loving it, without falling into jingoism but acknowledging its problems. For Manolo Sanlúcar, to be Andalusian was essentially a commitment, and few people have been as committed to our afflicted land as this artist from Sanlúcar de Barrameda who lived many years in El Pedroso, north of Seville, surrounded by oaks and trushes, by paintings of Baldomero Ressendi and by many memories, some more bitter than others, but all vivid.

Pastora Pavón, Niña de los Peines, the Empress of Cante, called him “my little kitty” due to his fuzzy hair when he was 15 years old, a time when he took part in the recording of Pastora’s last albums, now lost. At that early age, Manolo was a guitar prodigy pampered not just by Pastora and her husband, El Pinto, but also by Marchena, who was always admired by Manolo. He used to tell an anecdote about that Maestro de Maestros: when Marchena was on his deathbed at the hospital and the room’s light was turned off so he could die in peace, he told his wife, Isabelita Domínguez Cano: “Don’t turn the light off, because there is plenty of darkness I have yet to see”. Can darkness be seen? This is a question always pondered by Manolo, for whom depth was a quintessential Andalusian trait.

Manolo soon moved to the Spanish capital, like so many flamenco artists did, seeking a brighter future in its tablaos. It was Enrique Morente, the master from Granada, who told him to go back to Sanlúcar de Barrameda to create his own flamenco music away from the mundane noises, contemplating the ocean and Doñana’s pine forest. Manolo agreed, but when he arrived in Sanlúcar he saw that in place of a venerable tabern, one of those with a wooden bar and sherry barrels by the entrance, there was now a Burger King. He then understood why Morente told him to go back to his hometown, before it was too late.

He was perhaps the first flamenco guitarist to understand that flamenco could only be renewed through the guitar, through harmonies (…) Some of his productions, such as Medea, Trebujena and Tauromagia, are as well-known as the best works by Falla and Turina

He always knew that his music needed to have the taste and scent of the land, the true measure of musical purity, which is not defined by having a hoarse voice and a portrait of Juan Talega on the night table, like some purists like to believe. He tried all styles of guitar accompaniment, guiding bailaoras and cantaores with his guitar, but he wanted more. When his father put a guitar in his hands for the first time, looking intently into his eyes, without saying a word, he clearly understood his message. His father didn’t want him to follow his same steps, but to tread a different path, the one previously trod by Julián Arcas, Paco el Barbero, Ramón Montoya, Javier Molina and Niño Ricardo.

Manolo never forgot the sight of his father, Isidro, coming home at dawn, firing up the bread oven, tired, with the smell of expensive cigars and French perfume on his clothing. Isidro made a living playing the guitar in private parties, although he would occasionally perform on stages, too. Having grown up with a seasoned guitar player by his side, Manolo was committed since an early age to work hard to dignify the flamenco guitar and its players, to understand its world, its forms, to study its huge potential, to analyse its techniques and to create his own music.

He was perhaps the first flamenco guitarist to understand that flamenco could only be renewed through the guitar, through harmonies. That is why his first great album didn’t seek commercial success or self-promotion, but rather sought to review tradition, updating established forms while also creating new ones and opening new ways of expression. That is how the album Mundo y formas de la guitarra flamenca was born in 1972, a time when nostalgic and misinformed pseudo-intellectuals tried to find the origins of flamenco by putting microphones in caves and TV cameras in tenements.

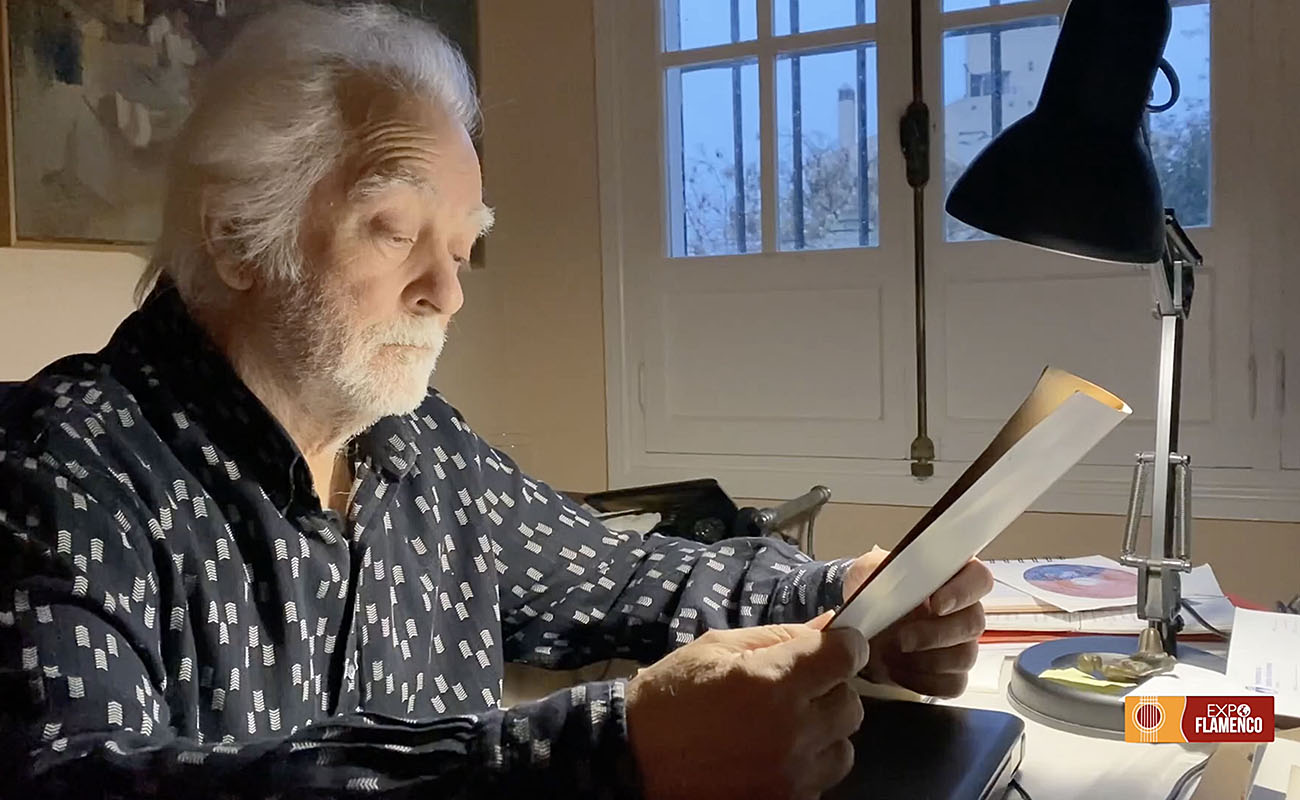

Manolo Sanlúcar created such a vast and important oeuvre that he could well have quit it all to enjoy a peaceful retirement raising chickens at his ranch. Some of his productions, such as Medea, Trebujena or Tauromagia, are as well-known as the best works by Falla o Turina. Yet, he continued working, composing and teaching. While other masters of the flamenco guitar spent many hours each day in airports showing nothing but their passports, this Andalusian who left us after 78 years, white-haired and tired of many things, until very recently would wake up each morning willing to teach us something. That is why he was our greatest flamenco artist.

Traslated by Paul Young