Remembering Pulpón

I think that when the 25th anniversary of the death of the artist’s agent Jesús Antonio Pulpón takes place, next year, the world of flamenco should pay a tribute to this great man. Yesterday, December 10, was the 24th anniversary of his death, and I remember that day as a very sad one. At the time I worked at Radio

I think that when the 25th anniversary of the death of the artist’s agent Jesús Antonio Pulpón takes place, next year, the world of flamenco should pay a tribute to this great man. Yesterday, December 10, was the 24th anniversary of his death, and I remember that day as a very sad one. At the time I worked at Radio Aljarafe, where I produced a popular, two-hour daily flamenco show. Pulpón used to listen to that show and he would call me now and then, annoyed at some criticism of his work, although I must confess he was always proper and respectful with the critics, because he understood the importance of the media for defending, dignifying and promoting flamenco.

Jesús Antonio Pulpón wasn’t the first great promoter of flamenco, as some people think, yet he was the most powerful of his time, as was the case, in earlier days, with Monserrat, his brother-in-law Vendrines or Pascual Saavedra, to name just the most renowned. While Vendrines belonged to the period of the Ópera Flamenca (from 1926 to 1936), Pulpón belonged to the time of the summer flamenco festivals, and it would be hard to conceive that period without him. Who could forget this great man arriving at the Potaje de Utrera, the Caracolá de Lebrija or the Festival de Cante Jondo Antonio Mairena, often carrying a black folder under his arm? He would arrive, pay the artists and rush to another festival, sometimes hundreds of miles away. That was Pulpón, a tireless worker.

Without a doubt, he was the most powerful man in flamenco, even commanding more power than Antonio Mairena, and that’s saying something. When so much power is yielded, though, it’s not easy being fair. Whoever disagreed with Pulpón often ended up sidelined. Whoever acted against him or his interests, did so at their own peril. Yet, if one day someone writes a biography about Pulpón (something that should be done), they ought to highlight his constant commitment to dignify flamenco and its artists. He was not only concerned with the big stars, but also with the lesser-known artists who would sing, dance or play the guitar with great purity, but were not suitable for the stages, something that in the earlier days of Monserrat and Vedrines would get them shunned.

What’s the role of the artist’s agents in an art such as flamenco? Frankly, they play a very important role, even as we sometimes perceive them as blood sucking parasites living off the artists. Like in all professions, there are all kinds of people, but I have met some agents that should be honored one day, and Pulpón is one of them, with all his flaws and virtues. He’s a man who started writing contracts on his bicycle and then became the most powerful man in flamenco.

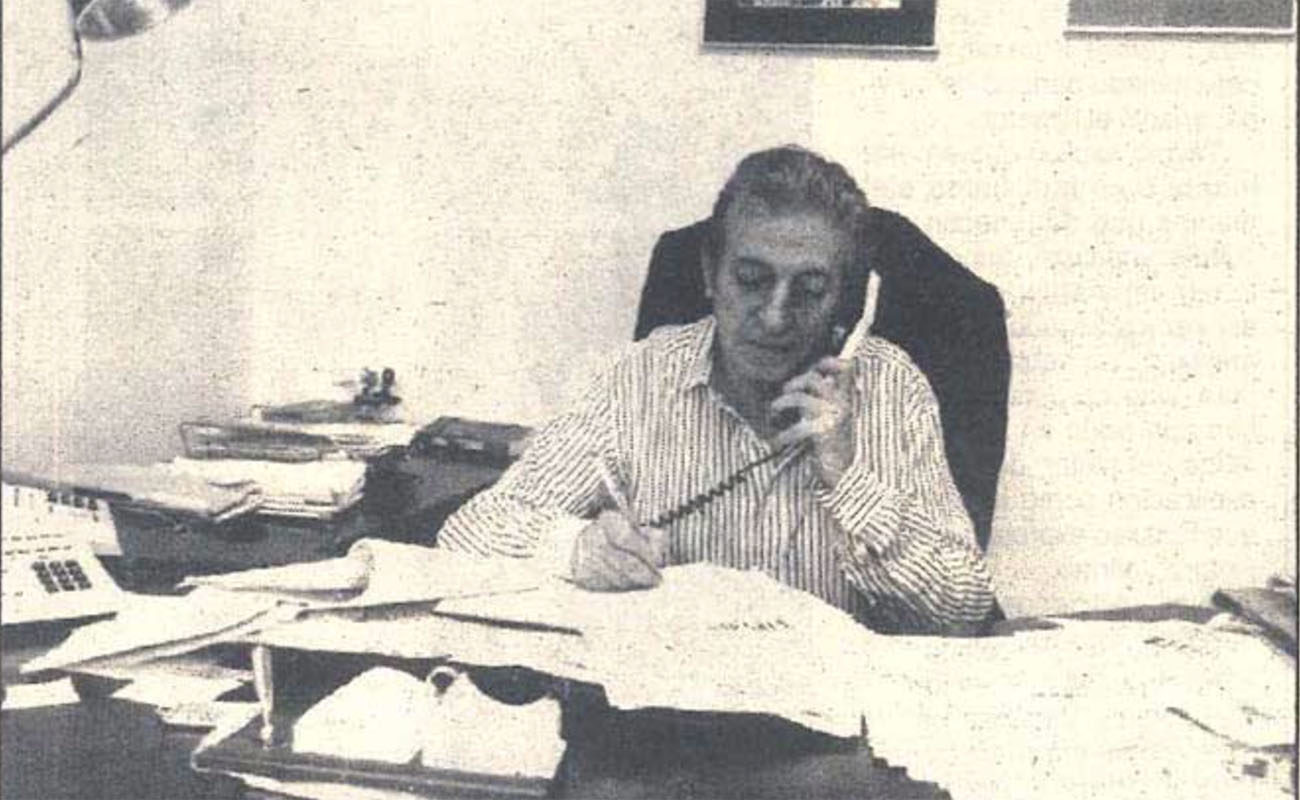

I would sometimes visit him at his office in La Campana, in the heart of the Old City district of Seville, and I was always welcomed with enthusiasm and kindness. Many fascinating things were discussed at his office. One morning, as I was waiting to meet him, I couldn’t help but listen to a conversation he was having at his office with a well-know flamenco star, who told him: “Antonio, I want to make something very clear: I want to work little, earn a lot, declare the essential to the taxman and only get the best gigs”. Pulpón wasn’t in a good mood and just answered him: “Then quit flamenco and go work for the government!”

You probably can figure out who was the big star. Don Jesús Antonio had to deal with some tough cookies.

Translated by P. Young