Why flamenco needs Pansequito

Flamenco needs Pansequito to constantly remind us this art-form is a sustainable renewable cultural resource when managed by knowledgeable individuals respectful of the genre.

I remember the day in 1974 when I was on my way out of a big store near the river in Málaga, and from the loudspeakers to the street this voice rang out. Little did I know Tápame tápame would go on to make history. I went back into the store. The guitars of Juan and Pepe Habichuela were launching razor blades of compás to anyone in earshot, and the voice of José Cortés Jiménez “Pansequito” (La Línea, 1946, raised in Puerto de Santa María), helped reconfigure forever our way of understanding cante.

I’d heard the singer’s name before, but not related it to any voice. Why was this such a defining moment? At that time, Camarón was the new kid on the block, attracting avid followers every day, flamenco fans both young and old, many of whom were tiring of the classic repertoire being repeated mimetically, with maestro Antonio Mairena casting a long shadow on the great flamenco landscape. I don’t recall anyone actively wishing for a changing of the guard, but these new voices, Camarón’s and Pansequito’s, came from two very young men, both in their mid-twenties, with the wizened delivery and textured voices of much older singers with life-lessons well-learned.

For a couple of years in the seventies, anyone claiming to be a flamenco fan had to choose sides – it’s a flamenco thing, like choosing a soccer team, Barsa or Real Madrid, Camarón or Pansequito. Thanks in part to the amazing guitar of Paco de Lucía, the scales tipped in favor of Camarón, not that he wasn’t a genius as well, but Paco’s involvement was an important factor. Today, Camarón is an eternal cult figure, while Pansequito is mostly remembered by flamenco fans of that specific generation.

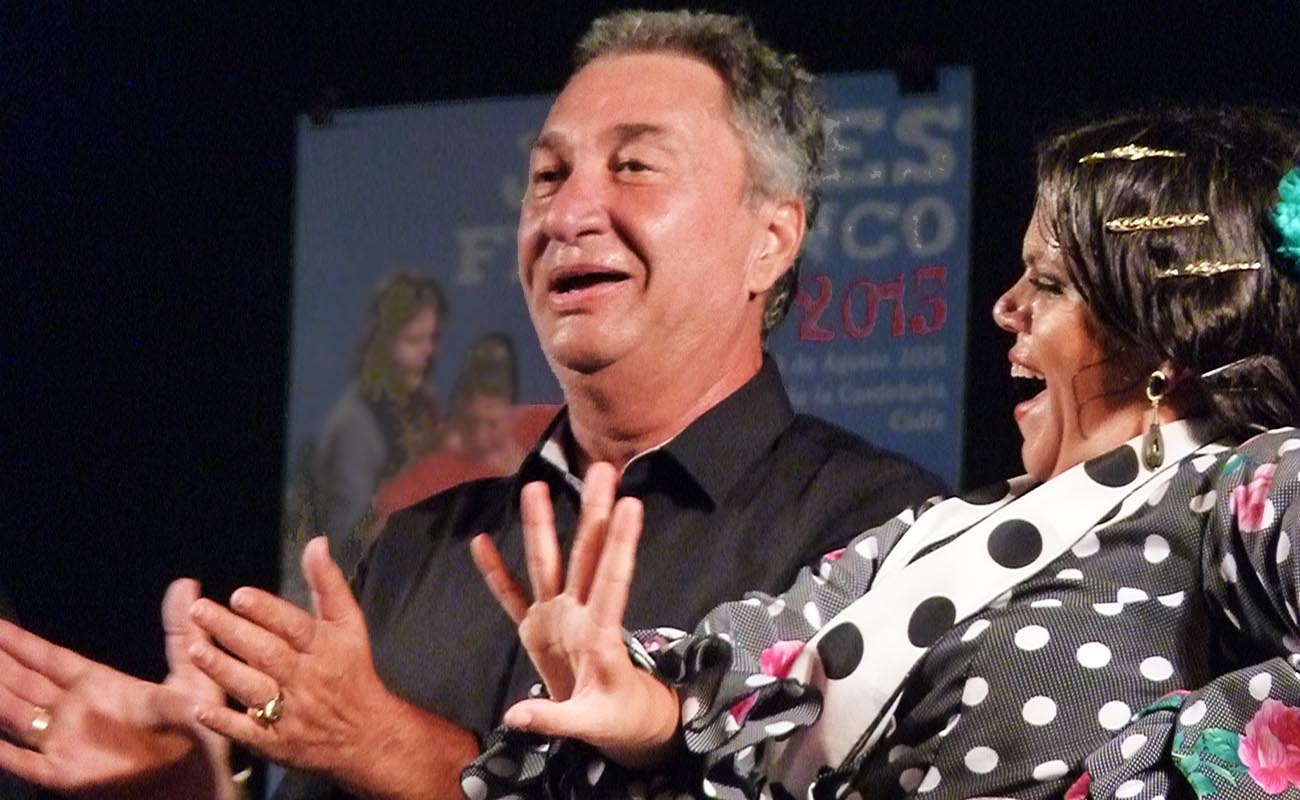

He recently gave a recital within the program of the Festival de Jerez, and his ardent followers showed up to nearly fill the venue. This man with the intensely flamenco delivery, needs no clenched fists or contorted grimaces, no shouting to get the message across. Great art of any kind thrives in subtlety and withers with histrionics.

Camarón has innumerable followers and imitators. With few exceptions, every flamenco singer of the past 40 years has graduated from that “school”. Pansequito has no followers, only die-hard admirers. Those haunting convoluted paths of melody that stretch out like a yo-yo taking dangerous curves, are not easily copied. Just when you’re sure the train is going to derail and you’re thinking of calling your mom to say you love her, Pansequito gets us back on track with a textbook landing, and it’s more thrilling than the giant roller coaster at Disneyland.

Some of his creations are perfect micro suites. Personalized verses and music that never stray from flamenco, while at the same time sounding fresh and innovative, a bridge between generations that would have been easily understood by singers a century ago, thanks to the lingua franca of this genre. Probably the most famous is the following perfect gem:

Es que la vía era mu’ corta

y mu’ largo era el camino

pero nadie sabe cuál es su sino

Dejadme flores, dejadme,

que yo voy al campito a divertirme

que el campo no tiene llave

[Life is so short and the road is so long, but no one knows their fate, leave me flowers, I’m headed for the countryside to enjoy myself, the fields have no locks]

That composition, and its peculiar interpretation, is a fleeting but brilliant moment in flamenco singing of the twentieth century. A highly stylized creation based on classic verses by one of the singers with the biggest personality of our time.

Pansequito nourishes flamenco while also feeding on it, simultaneously original and classic. In addition to his buoyant bulerías, there are the luminous cantiñas, dense tarantos, sober soleá and siguiriyas, undulating tangos… The man shows us what can be done with cante, abstaining from strange detours that would fail to enthrall.

Flamenco needs Pansequito to constantly remind us this art-form is a sustainable renewable cultural resource when managed by knowledgeable individuals respectful of the genre. Like Duke Ellington said, if you don’t know the rules, you shouldn’t break them.

They got it right at the Córdoba National Contest that time when the prize for creativity was hastily organized in order to accommodate the outsized talent and keen instincts of this man with the seductive flamenco voice.