40 years in cante

Flamenco grabs and doesn’t let go. We die with flamenco inside, and when we leave this world, I suppose we would regret having missed that genius of cante, baile or toque who wasn't born yet

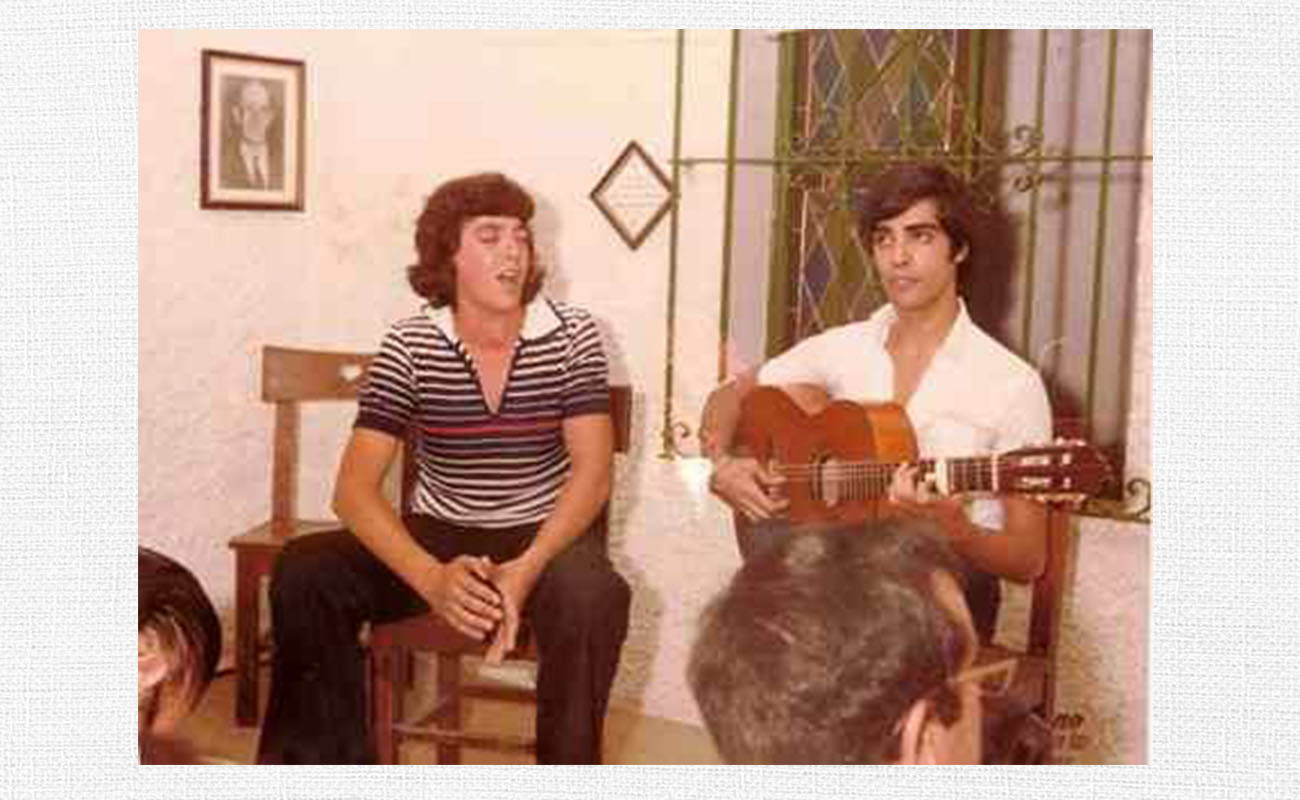

These days I celebrate the 40th anniversary of my relationship with flamenco, which started when I was 17 (now you know how old I am.) Actually, it started much earlier, when I was a little kid in Palomares del Río, near Seville, where I used to listen to my mother singing those post-war milongas while she did laundry in the earthenware bowl in our yard. It was there too where I’d be fascinated listening to stirring stories told by old men with plonk-burnt voices. When I was 17, though, I moved to a neighborhood of Seville, Su Eminencia, where the Peña Flamenca El Chozas was founded (and it’s still there today). That’s where everything started. At night, as I tried to sleep, I listened to the aficionados singing in that peña, and something called me. I got up from bed, got dressed, and went to that place, to check what was that thing that made my chest ache and made me think of things that had never crossed my mind, which moved me unlike anything else I had experienced before.

The first cantaor I started following was precisely El Chozas, the peña’s namesake (not to be confused with El Chozas de Lebrija). He was a new cantaor from the Los Carteros neighborhood in Seville, who had just released his first album (the first LP I’d ever bought). Later in that peña I heard cantaores such as Antonio Mairena and his brother Manuel, Naranjito de Triana, Luis Caballero, Lebrijano, Niño de Fregenal, el Gordito de Triana and Cepero de Cantillana, among many others. All of them got me into cante, and I wanted to become a cantaor. However, I had to give that up, as I would start sweating like a pig as soon as I heard the first notes of the guitar. I could not sing in front of an audience. One night I tried, in a contest at the Peña Flamenca del Cerro del Águila, in Seville. I sang with my eyes closed, and when I opened them, I saw that most of the public had left already. That’s when I decided to become a flamenco critic, when I was 20 years old. That was thirty-seven years ago, and I’m still here, with twelve books published and thousands of articles written in festivals and theaters all over the world. I could say that I still write with the same illusion as I had in my first day, which would sound nice, but the truth is that I feel a bit tired. Sometimes I reach the conclusion that there is no point in writing about an art that is so complex and difficult, but then I play something by Tomás Pavón or Manuel Vallejo and it all makes perfect sense.

I cannot live without flamenco, not the least because it has become my profession. I’m one of the few professional critics that makes a living exclusively from writing, in a country, Spain, where writing is crying. My whole life revolves around flamenco: I get up every morning thinking what I will write, and what I’ll listen to, and I get in bed thinking about all I’ve done through the day, unable to get to sleep, with some compás stuck in my head and the verses of a soleá inviting me to sing with passion. Flamenco grabs and doesn’t let go. We die with flamenco inside, and when we leave this world, I suppose we would regret having missed that genius of cante, baile or toque who wasn’t born yet. I apologize for having bored you today with this article, instead of having written about some current event, but I had to share with you all the emotion of being for four decades attached to an art which totally changed my life and allowed me to meet geniuses like Valderrama, Mairena, Sabicas, Morente, Camarón, Farruco, Paco de Lucía or Manolo Sanlúcar. It’s a privilege which I’m not sure I deserve, but which I appreciate with all my soul. I’ll be still here through thick and thin, as far as my body can stand, defending flamenco.

* This article was originally published on October 7th, 2015